Caribbean

The Caribbean (/ˌkærɪˈbiːən, kəˈrɪbiən/, locally /ˈkærɪbiæn/;[5] Spanish: Caribe; French: Caraïbes; Haitian Creole: Karayib; also Antillean Creole: Kawayib; Dutch: Caraïben; Papiamento: Karibe) is a region of the Americas that comprises the Caribbean Sea, its surrounding coasts, and its islands (some of which lie within the Caribbean Sea[6] and some of which lie on the edge of the Caribbean Sea where it borders the North Atlantic Ocean).[7] The region lies southeast of the Gulf of Mexico and of the North American mainland, east of Central America, and north of South America.

The region, situated largely on the Caribbean Plate, has more than 700 islands, islets, reefs and cays (see the list of Caribbean islands). Three island arcs delineate the eastern and northern edges of the Caribbean Sea:[8] The Greater Antilles to the north, and the Lesser Antilles and Leeward Antilles to the south and east. Together with the nearby Lucayan Archipelago, these island arcs make up the West Indies. The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands are sometimes considered to be a part of the Caribbean, even though they are neither within the Caribbean Sea nor on its border. However, The Bahamas is a full member state of the Caribbean Community and the Turks and Caicos Islands are an associate member. Belize, Guyana, and Suriname are also considered part of the Caribbean despite being mainland countries and they are full member states of the Caribbean Community and the Association of Caribbean States. Several regions of mainland North and South America are also often seen as part of the Caribbean because of their political and cultural ties with the region. These include Belize, the Caribbean region of Colombia, the Venezuelan Caribbean, Quintana Roo in Mexico (consisting of Cozumel and the Caribbean coast of the Yucatán Peninsula),[4] and The Guianas (Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Guayana Region in Venezuela, and Amapá in Brazil).[9]

A mostly tropical geography, the climates are greatly shaped by sea temperatures and precipitation, with the hurricane season regularly leading to natural disasters. Because of its tropical climate and low-lying island geography, the Caribbean is vulnerable to a number of climate change effects, including increased storm intensity, saltwater intrusion, sea level rise and coastal erosion, and precipitation variability.[10] These weather changes will greatly change the economies of the islands, and especially the major industries of agriculture and tourism.[10]

The Caribbean was occupied by indigenous people since at least 6000 BC.[11] When European settlement followed the arrival of Columbus in Hispaniola, the Spanish established the first permanent colony in the region, and the native population was quickly decimated by brutal labour practices, enslavement and disease. Europeans supplanted the natives with enslaved Africans in most islands.[12]: 4–6 Following the independence of Haiti from France in the early 19th century and the decline of slavery in the 19th century, island nations in the Caribbean gradually gained independence, with a wave of new states during the 1950s and 60s. Because of the proximity to the United States, there is also a long history of United States intervention in the region's affairs.[13][14] In 1823 former United States President James Monroe formulated a new policy strategy that has since come to be known as the Monroe Doctrine over the hemisphere, it concludes that the United States places limits on Europe's on-going affairs and involvement within the hemisphere.[15]

The islands of the Caribbean (the West Indies) are often regarded as a subregion of North America, though sometimes they are included in Middle America or then left as a subregion of their own[16][17] and are organized into 30 territories including sovereign states, overseas departments, and dependencies. From 15 December 1954, to 10 October 2010, there was a country known as the Netherlands Antilles composed of five states, all of which were Dutch dependencies.[18] From 3 January 1958, to 31 May 1962, there was also a political union called the British West Indies Federation composed of ten English-speaking Caribbean provinces, all of which were then British dependencies.

Etymology and pronunciation

The region takes its name from that of the Caribs, an ethnic group present in the Lesser Antilles and parts of adjacent South America at the time of the Spanish conquest of the Americas.[19] The term was popularized by British cartographer Thomas Jefferys who used it in his The West-India Atlas (1773).[20]

The two most prevalent pronunciations of "Caribbean" outside the Caribbean are /ˌkærɪˈbiːən/ (KARR-ə-BEE-ən), with the primary stress on the third syllable, and /kəˈrɪbiən/ (kə-RIB-ee-ən), with the stress on the second. Most authorities of the last century preferred the stress on the third syllable.[21] This is the older of the two pronunciations, but the stressed-second-syllable variant has been established for over 75 years.[22] It has been suggested that speakers of British English prefer /ˌkærɪˈbiːən/ (KARR-ə-BEE-ən) while North American speakers more typically use /kəˈrɪbiən/ (kə-RIB-ee-ən),[23] but major American dictionaries and other sources list the stress on the third syllable as more common in American English too.[24][25][26][27] According to the American version of Oxford Online Dictionaries, the stress on the second syllable is becoming more common in UK English and is increasingly considered "by some" to be more up to date and more "correct".[28]

The Oxford Online Dictionaries claim that the stress on the second syllable is the most common pronunciation in the Caribbean itself, but according to the Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage, the most common pronunciation in Caribbean English stresses the first syllable instead, /ˈkærɪbiæn/ (KARR-ih-bee-an).[5][28] The word Caribbean consistently ranks as one of the most misspelled words in the English language.[29][30]

Definition

The word "Caribbean" has multiple uses. Its principal ones are geographical and political. The Caribbean can also be expanded to include territories with strong cultural and historical connections to Africa, slavery, European colonisation and the plantation system.

- The United Nations geoscheme for the Americas presents the Caribbean as a distinct region within the Americas.

- Physiographically, the Caribbean region is mainly a chain of islands surrounding the Caribbean Sea. To the north, the region is bordered by the Gulf of Mexico, the Straits of Florida and the Northern Atlantic Ocean, which lies to the east and northeast. To the south lies the coastline of the continent of South America.

- Politically, the "Caribbean" may be centred by considering narrower and wider socio-economic groupings:

- At its core is the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), whose full members include the Commonwealth of the Bahamas in the Atlantic, the Co-operative Republic of Guyana and the Republic of Suriname in South America, and Belize in Central America; its associate members include Bermuda and the Turks and Caicos Islands in the Atlantic Ocean.

- Most expansive is the Association of Caribbean States (ACS), which includes almost every nation in the region surrounding the Caribbean and also El Salvador on the Pacific Ocean. According to the ACS, the total population of its member states is 227 million people.[31]

Countries and territories

History

The oldest evidence of humans in the Caribbean is in southern Trinidad at Banwari Trace, where remains have been found from seven thousand years ago.[11] These pre-ceramic sites, which belong to the Archaic (pre-ceramic) age, have been termed Ortoiroid. The earliest archaeological evidence of human settlement in Hispaniola dates to about 3600 BC, but the reliability of these finds is questioned. Consistent dates of 3100 BC appear in Cuba. The earliest dates in the Lesser Antilles are from 2000 BC in Antigua. A lack of pre-ceramic sites in the Windward Islands and differences in technology suggest that these Archaic settlers may have Central American origins. Whether an Ortoiroid colonization of the islands took place is uncertain, but there is little evidence of one.

Between 400 BC and 200 BC the first ceramic-using agriculturalists, the Saladoid culture, entered Trinidad from South America. They expanded up the Orinoco River to Trinidad and then spread rapidly up the islands of the Caribbean. Some time after 250 AD another group, the Barancoid, entered Trinidad. The Barancoid society collapsed along the Orinoco around 650 AD and another group, the Arauquinoid, expanded into these areas and up the Caribbean chain. Around 1300 AD a new group, the Mayoid, entered Trinidad and remained the dominant culture until Spanish settlement.

At the time of the European discovery of most of the islands of the Caribbean, three major Amerindian indigenous peoples lived on the islands: the Taíno in the Greater Antilles, the Bahamas and the Leeward Islands, the Island Caribs in the Windward Islands, and the Guanahatabey in western Cuba. The Taínos are subdivided into Classic Taínos, who occupied Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, Western Taínos, who occupied Cuba, Jamaica, and the Bahamian archipelago, and the Eastern Taínos, who occupied the Leeward Islands. Trinidad was inhabited by both Carib speaking and Arawak-speaking groups.

Soon after Christopher Columbus came to the Caribbean, both Portuguese and Spanish explorers began claiming territories in Central and South America. These early colonies brought gold to Europe; most specifically England, the Netherlands, and France. These nations hoped to establish profitable colonies in the Caribbean. Colonial rivalries made the Caribbean a cockpit for European wars for centuries.

The Caribbean was known for pirates, especially between 1640 and 1680. The term "buccaneer" is often used to describe a pirate operating in this region. The Caribbean region was war-torn throughout much of its colonial history, but the wars were often based in Europe, with only minor battles fought in the Caribbean. Some wars, however, were born of political turmoil in the Caribbean itself.

Haiti was the first Caribbean nation to gain independence from European powers (see Haitian Revolution). Some Caribbean nations gained independence from European powers in the 19th century. Some smaller states are still dependencies of European powers today. Cuba remained a Spanish colony until the Spanish–American War. Between 1958 and 1962, most of the British-controlled Caribbean became the West Indies Federation before they separated into many separate nations.

Foreign interventions by the United States

The United States has conducted military operations in the Caribbean and Latin America regions for at least 100 years.[40] Successive administrations of the Caribbean region have regularly maintained that the Caribbean must remain a zone of peace and have sought declarations at the United Nations to declare the region as such.

Since the Monroe Doctrine, the United States gained a major influence on most Caribbean nations. In the early part of the 20th century, this influence was extended by participation in the Banana Wars. Victory in the Spanish–American War and the signing of the Platt Amendment in 1901 ensured that the United States would have the right to interfere in Cuban political and economic affairs, militarily if necessary. With the Treaty of Paris, Spain ceded control of Cuba and Puerto Rico to the United States. Thereafter, the United States conducted military interventions in Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. The series of conflicts ended with the withdrawal of troops from Haiti in 1934 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, relations deteriorated rapidly leading to the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and successive US attempts to destabilize the island, based upon Cold War fears of the Soviet threat. The U.S. invaded and occupied Haiti for 19 years (1915–34), subsequently dominating the Haitian economy through aid and loan repayments. The U.S. invaded Haiti again in 1994 to overthrow a military regime, and restored elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. In the 2004, Aristide was overthrown in coup d'état, and flown out of the country by the U.S.. Aristide later accused the U.S of kidnapping him. In 1965, 23,000 US troops were sent to the Dominican Republic to intervene into the Dominican Civil War to end the war and prevent supporters of supporters of deposed left-wing president Juan Bosch taking over. President Lyndon Johnson had ordered the invasion to stem what he deemed to be a "Communist threat". On October 25 1983, the United States invaded Grenada to remove left-wing leader Hudson Austin, who had deposed Maurice Bishop nine days earlier on October 16. Bishop was executed three days later on the 19th.[41] The US maintains a naval military base in Cuba at Guantanamo Bay. The base is one of five unified commands whose "area of responsibility" is Latin America and the Caribbean. The command is headquartered in Miami, Florida.

Counter-attack by Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces supported by T-34 tanks near Playa Giron during the Bay of Pigs Invasion, 19 April 1961.

Counter-attack by Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces supported by T-34 tanks near Playa Giron during the Bay of Pigs Invasion, 19 April 1961..jpg.webp) A Marine heavy machine gunner monitors a position along the international neutral corridor in Santo Domingo, 1965.

A Marine heavy machine gunner monitors a position along the international neutral corridor in Santo Domingo, 1965. A Soviet-made BTR-60 armored personnel carrier seized by US forces during Operation Urgent Fury (1983)

A Soviet-made BTR-60 armored personnel carrier seized by US forces during Operation Urgent Fury (1983)_off_Haiti_in_1994.JPEG.webp) US Army Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk, Bell AH-1 Cobra and Bell OH-58 Kiowa helicopters on the deck of the US Navy aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) off Haiti, 1994.

US Army Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk, Bell AH-1 Cobra and Bell OH-58 Kiowa helicopters on the deck of the US Navy aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) off Haiti, 1994.

Foreign interventions by Cuba

From 1966 until the late 1980s, the Soviet government upgraded Cuba's military capabilities, and Cuban leader Fidel Castro saw to it that Cuba assisted with the independence struggles of several countries across the world, most notably Angola and Mozambique in southern Africa, and the anti-imperialist struggles of countries such as Syria, Algeria, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Vietnam.[42][43] Its Angolan involvement was particularly intense and noteworthy with heavy assistance given to the Marxist–Leninist MPLA in the Angolan Civil War. Cuba sent 380,000 troops to Angola and 70,000 additional civilian technicians and volunteers. (The Cuban forces possessed 1,000 tanks, 600 armoured vehicles and 1,600 artillery pieces.)

Cuba's involvement in the Angolan Civil War began in the 1960s when relations were established with the leftist Movement for the Popular Liberation of Angola (MPLA). The MPLA was one of three organizations struggling to gain Angola's independence from Portugal, the other two being UNITA and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA). In August and October 1975, the South African Defence Force (SADF) intervened in Angola in support of the UNITA and FNLA. On 14 October 1975, the SADF commenced Operation Savannah in an effort to capture Luanda from the south. On 5 November 1975, without consulting Moscow, the Cuban government opted for direct intervention with combat troops (Operation Carlota) in support of the MPLA and the combined MPLA-Cuban armies managed to stop the South African advance by 26 November.

During the Ogaden War (1977–78) in which Somalia attempted to invade an Ethiopia affected by civil war, Cuba deployed 18,000 troops along with armoured vehicles, artillery, T-62 tanks, and MiGs to assist the Derg. Ethiopia and Cuba defeated Somalia on 9 March 1978.[44]

In 1987–88, South Africa again sent military forces to Angola to stop an advance of MPLA forces (FAPLA) against UNITA, leading to the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, where the SADF was unable to defeat the FAPLA and Cuban forces. Cuba also directly participated in the negotiations between Angola and South Africa, again without consulting Moscow. Within two years, the Cold War was over and Cuba's foreign policy shifted away from military intervention.

Geography and geology

.svg.png.webp)

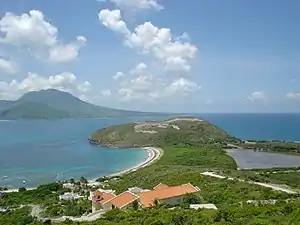

The geography and climate in the Caribbean region varies: Some islands in the region have relatively flat terrain of non-volcanic origin. These islands include Aruba (possessing only minor volcanic features), Curaçao, Barbados, Bonaire, the Cayman Islands, Saint Croix, the Bahamas, and Antigua. Others possess rugged towering mountain-ranges like the islands of Saint Martin, Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Dominica, Montserrat, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Saint Kitts, Saint Lucia, Saint Thomas, Saint John, Tortola, Grenada, Saint Vincent, Guadeloupe, Martinique and Trinidad and Tobago.

Definitions of the terms Greater Antilles and Lesser Antilles often vary. The Virgin Islands as part of the Puerto Rican bank are sometimes included with the Greater Antilles. The term Lesser Antilles is often used to define an island arc that includes Grenada but excludes Trinidad and Tobago and the Leeward Antilles.

The waters of the Caribbean Sea host large, migratory schools of fish, turtles, and coral reef formations. The Puerto Rico Trench, located on the fringe of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea just to the north of the island of Puerto Rico, is the deepest point in all of the Atlantic Ocean.[45]

The region sits in the line of several major shipping routes with the Panama Canal connecting the western Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean.

Island groups

Lucayan Archipelago[lower-alpha 1]

The Bahamas

The Bahamas Turks and Caicos Islands (United Kingdom)

Turks and Caicos Islands (United Kingdom)

Cayman Islands (United Kingdom)

Cayman Islands (United Kingdom) Cuba

Cuba- Hispaniola, politically divided between:

Jamaica

Jamaica Puerto Rico (United States)

Puerto Rico (United States)

- Leeward Islands

United States Virgin Islands (United States)

United States Virgin Islands (United States)

British Virgin Islands (United Kingdom)

British Virgin Islands (United Kingdom)

Anguilla (United Kingdom)

Anguilla (United Kingdom) Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda

- Saint Martin, politically divided between

Saint Martin (France)

Saint Martin (France) Sint Maarten (Kingdom of the Netherlands)

Sint Maarten (Kingdom of the Netherlands)

Saba (Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands)

Saba (Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands) Sint Eustatius (Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands)

Sint Eustatius (Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands) Saint Barthélemy (French Antilles, France)

Saint Barthélemy (French Antilles, France) Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Montserrat (United Kingdom)

Montserrat (United Kingdom) Guadeloupe (French Antilles, France) including

Guadeloupe (French Antilles, France) including

- Windward Islands

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago

- Leeward Antilles

Aruba (Kingdom of the Netherlands)

Aruba (Kingdom of the Netherlands) Curaçao (Kingdom of the Netherlands)

Curaçao (Kingdom of the Netherlands) Bonaire (Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands)

Bonaire (Caribbean Netherlands, Netherlands)

Historical groupings

All islands at some point were, and a few still are, colonies of European nations; a few are overseas or dependent territories:

- British West Indies/Anglophone Caribbean – Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Bay Islands, Guyana, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Croix (briefly), Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago (from 1797) and the Turks and Caicos Islands

- Danish West Indies – Possession of Denmark-Norway before 1814, then Denmark, present-day United States Virgin Islands

- Dutch West Indies – Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Sint Maarten, Bay Islands (briefly), Saint Croix (briefly), Tobago, Surinam and Virgin Islands

- French West Indies – Anguilla (briefly), Antigua and Barbuda (briefly), Dominica, Dominican Republic (briefly), Grenada, Haiti (formerly Saint-Domingue), Montserrat (briefly), Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sint Eustatius (briefly), Sint Maarten, Saint Kitts (briefly), Tobago (briefly), Saint Croix, the current French overseas départements of French Guiana, Martinique and Guadeloupe (including Marie-Galante, La Désirade and Les Saintes), the current French overseas collectivities of Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin

- Portuguese West Indies – present-day Barbados, known as Os Barbados in the 16th century when the Portuguese claimed the island en route to Brazil. The Portuguese left Barbados abandoned years before the British arrived.

- Spanish West Indies – Cuba, Hispaniola (present-day Dominican Republic, Haiti (until 1659, lost to France)), Puerto Rico, Jamaica (until 1655, lost to Great Britain), the Cayman Islands (until 1670 to Great Britain) Trinidad (until 1797, lost to Great Britain) and Bay Islands (until 1643, lost to Great Britain), coastal islands of Central America (except Belize), and some Caribbean coastal islands of Panama, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela.

- Swedish West Indies – present-day French Saint-Barthélemy, Guadeloupe (briefly) and Tobago (briefly).

- Courlander West Indies – Tobago (until 1691)

The British West Indies were united by the United Kingdom into a West Indies Federation between 1958 and 1962. The independent countries formerly part of the B.W.I. still have a joint cricket team that competes in Test matches, One Day Internationals and Twenty20 Internationals. The West Indian cricket team includes the South American nation of Guyana, the only former British colony on the mainland of that continent.

Continental countries with Caribbean coastlines and islands

|

* Disputed territories administered by Colombia.

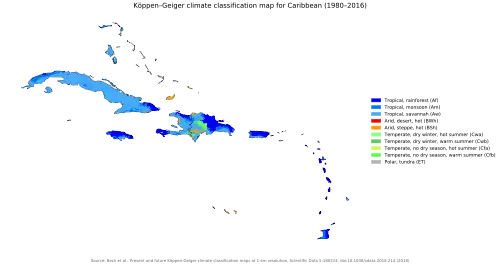

Climate

The climate of the area is tropical, varying from tropical rainforest in some areas to tropical monsoon and tropical savanna in others. There are also some locations that are arid climates with considerable drought in some years, and the peaks of mountains tend to have cooler temperate climates.

Rainfall varies with elevation, size and water currents, such as the cool upwellings that keep the ABC islands arid. Warm, moist trade winds blow consistently from the east, creating both rain forest and semi-arid climates across the region. The tropical rainforest climates include lowland areas near the Caribbean Sea from Costa Rica north to Belize, as well as the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, while the more seasonal dry tropical savanna climates are found in Cuba, northern Colombia and Venezuela, and southern Yucatán, Mexico. Arid climates are found along the extreme northern coast of Venezuela out to the islands including Aruba and Curacao, as well as the northwestern tip of Yucatán.

While the region generally is sunny much of the year, the wet season from May through November sees more frequent cloud cover (both broken and overcast), while the dry season from December through April is more often clear to mostly sunny. Seasonal rainfall is divided into 'dry' and 'wet' seasons, with the latter six months of the year being wetter than the first half. The air temperature is hot much of the year, varying from 25 to 33 °C (77 to 91 °F) between the wet and dry seasons. Seasonally, monthly mean temperatures vary from only about 5 °C (9 °F) in the northernmost regions, to less than 3 °C (5 °F) in the southernmost areas of the Caribbean.

Hurricane season is from June to November, but they occur more frequently in August and September and more common in the northern islands of the Caribbean. Hurricanes that sometimes batter the region usually strike northwards of Grenada and to the west of Barbados. The principal hurricane belt arcs to the northwest of the island of Barbados in the Eastern Caribbean. A great example being recent events of Hurricane Irma devastating the island of Saint Martin during the 2017 hurricane season.

Sea surface temperatures change little annually, normally running from 30 °C (86 °F) in the warmest months to 26 °C (79 °F) in the coolest months. The air temperature is warm year-round, in the 20s and 30s °C (70s, 80s, and 90s °F), and varies only from winter to summer about 2–5 degrees on the southern islands and about a 10–20 degrees difference on the northern islands of the Caribbean. The northern islands, like the Bahamas, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic, may be influenced by continental masses during winter months, such as cold fronts.

Dominican Republic: Latitude 18°N

| Climate data for Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.0 (98.6) |

39.5 (103.1) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

36.7 (98.1) |

38.8 (101.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.4 (84.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.7 (76.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 74.5 (2.93) |

67.9 (2.67) |

61.9 (2.44) |

72.1 (2.84) |

176.6 (6.95) |

116.4 (4.58) |

131.2 (5.17) |

178.1 (7.01) |

208.7 (8.22) |

186.2 (7.33) |

132.5 (5.22) |

82.9 (3.26) |

1,489 (58.62) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.3 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 10.5 | 9.3 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 12.5 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 115.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.0 | 81.1 | 80.1 | 79.4 | 82.2 | 82.2 | 82.2 | 83.3 | 84.0 | 84.8 | 84.0 | 82.6 | 82.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 239.7 | 229.6 | 253.4 | 248.8 | 233.9 | 232.3 | 225.9 | 231.6 | 219.9 | 230.7 | 227.5 | 224.1 | 2,797.4 |

| Source: ONAMET[46] | |||||||||||||

Aruba: Latitude 12°N

| Climate data for Oranjestad, Aruba (1981–2010, extremes 1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.7 (80.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.3 (1.55) |

20.6 (0.81) |

8.7 (0.34) |

11.6 (0.46) |

16.3 (0.64) |

18.7 (0.74) |

31.7 (1.25) |

25.8 (1.02) |

45.5 (1.79) |

77.8 (3.06) |

94.0 (3.70) |

81.8 (3.22) |

471.8 (18.58) |

| Source: DEPARTAMENTO METEOROLOGICO ARUBA,[47] (extremes)[48] | |||||||||||||

Puerto Rico: Latitude 18°N

| Climate data for San Juan, Puerto Rico | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33 (92) |

36 (96) |

36 (96) |

36 (97) |

36 (96) |

36 (97) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

36 (97) |

36 (97) |

37 (98) |

36 (96) |

34 (94) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28 (83) |

29 (84) |

29 (85) |

30 (86) |

31 (87) |

32 (89) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

32 (89) |

31 (88) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

23 (74) |

24 (76) |

26 (78) |

26 (78) |

26 (78) |

26 (78) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 16 (61) |

17 (62) |

16 (60) |

18 (64) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

21 (69) |

20 (68) |

21 (69) |

19 (67) |

18 (65) |

17 (62) |

16 (61) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 95 (3.7) |

60 (2.4) |

49 (1.9) |

118 (4.6) |

150 (5.9) |

112 (4.4) |

128 (5.0) |

138 (5.4) |

146 (5.7) |

142 (5.6) |

161 (6.3) |

126 (5.0) |

1,431 (56.3) |

| Source: The National Weather Service[49] | |||||||||||||

Cuba: at Latitude 22°N

| Climate data for Havana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.9 (98.4) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.1 (79.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 64.4 (2.54) |

68.6 (2.70) |

46.2 (1.82) |

53.7 (2.11) |

98.0 (3.86) |

182.3 (7.18) |

105.6 (4.16) |

99.6 (3.92) |

144.4 (5.69) |

180.5 (7.11) |

88.3 (3.48) |

57.6 (2.27) |

1,189.2 (46.84) |

| Source: World Meteorological Organisation (UN),[50] Climate-Charts.com[51] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Biodiversity

The Caribbean islands have some of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. The animals, fungi, and plants have been classified as one of Conservation International's biodiversity hotspots because of their exceptionally diverse terrestrial and marine ecosystems, ranging from montane cloud forests, to tropical rainforest, to cactus scrublands. The region also contains about 8% (by surface area) of the world's coral reefs[59] along with extensive seagrass meadows,[60] both of which are frequently found in the shallow marine waters bordering the island and continental coasts of the region.

For the fungi, there is a modern checklist based on nearly 90,000 records derived from specimens in reference collections, published accounts, and field observations.[61] That checklist includes more than 11,250 species of fungi recorded from the region. As its authors note, the work is far from exhaustive, and it is likely that the true total number of fungal species already known from the Caribbean is higher. The true total number of fungal species occurring in the Caribbean, including species not yet recorded, is likely far higher given the generally accepted estimate that only about 7% of all fungi worldwide have been discovered.[62] Though the amount of available information is still small, a first effort has been made to estimate the number of fungal species endemic to some Caribbean islands. For Cuba, 2200 species of fungi have been tentatively identified as possible endemics of the island;[63] for Puerto Rico, the number is 789 species;[64] for the Dominican Republic, the number is 699 species;[65] for Trinidad and Tobago, the number is 407 species.[66]

Many of the ecosystems of the Caribbean islands have been devastated by deforestation, pollution, and human encroachment. The arrival of the first humans is correlated with extinction of giant owls and dwarf ground sloths.[67] The hotspot contains dozens of highly threatened animals (ranging from birds, to mammals and reptiles), fungi and plants. Examples of threatened animals include the Puerto Rican amazon, two species of solenodon (giant shrews) in Cuba and Hispaniola, and the Cuban crocodile.

The region's coral reefs, which contain about 70 species of hard corals and between 500 and 700 species of reef-associated fishes[68] have undergone rapid decline in ecosystem integrity in recent years, and are considered particularly vulnerable to global warming and ocean acidification.[69] According to a UNEP report, the Caribbean coral reefs might get extinct in next 20 years due to population explosion along the coast lines, overfishing, the pollution of coastal areas and global warming.[70]

Some Caribbean islands have terrain that Europeans found suitable for cultivation for agriculture. Tobacco was an important early crop during the colonial era, but was eventually overtaken by sugarcane production as the region's staple crop. Sugar was produced from sugarcane for export to Europe. Cuba and Barbados were historically the largest producers of sugar. The tropical plantation system thus came to dominate Caribbean settlement. Other islands were found to have terrain unsuited for agriculture, for example Dominica, which remains heavily forested. The islands in the southern Lesser Antilles, Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, are extremely arid, making them unsuitable for agriculture. However, they have salt pans that were exploited by the Dutch. Seawater was pumped into shallow ponds, producing coarse salt when the water evaporated.[71]

The natural environmental diversity of the Caribbean islands has led to recent growth in eco-tourism. This type of tourism is growing on islands lacking sandy beaches and dense human populations.[72]

Plants and animals

.jpg.webp) Epiphytes (bromeliads, climbing palms) in the rainforest of Dominica.

Epiphytes (bromeliads, climbing palms) in the rainforest of Dominica. A green and black poison frog, Dendrobates auratus

A green and black poison frog, Dendrobates auratus Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Guadeloupe.

Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Guadeloupe. Costus speciosus, a marsh plant, Guadeloupe.

Costus speciosus, a marsh plant, Guadeloupe..jpg.webp) An Atlantic ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata) in Martinique.

An Atlantic ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata) in Martinique. Crescentia cujete, or calabash fruit, Martinique.

Crescentia cujete, or calabash fruit, Martinique._juvenile_yellow_stage_over_Bispira_brunnea_(Social_Feather_Duster_Worms).jpg.webp) Thalassoma bifasciatum (bluehead wrasse fish), over Bispira brunnea (social feather duster worms).

Thalassoma bifasciatum (bluehead wrasse fish), over Bispira brunnea (social feather duster worms)..jpg.webp) Two Stenopus hispidus (banded cleaner shrimp) on a Xestospongia muta (giant barrel sponge).

Two Stenopus hispidus (banded cleaner shrimp) on a Xestospongia muta (giant barrel sponge)._pair.jpg.webp) A pair of Cyphoma signatum (fingerprint cowry), off coastal Haiti.

A pair of Cyphoma signatum (fingerprint cowry), off coastal Haiti. The Martinique amazon, Amazona martinicana, is an extinct species of parrot in the family Psittacidae.

The Martinique amazon, Amazona martinicana, is an extinct species of parrot in the family Psittacidae. Anastrepha suspensa, a Caribbean fruit fly.

Anastrepha suspensa, a Caribbean fruit fly..jpg.webp) Hemidactylus mabouia, a tropical gecko, in Dominica Edited by: Taniya Brooks.

Hemidactylus mabouia, a tropical gecko, in Dominica Edited by: Taniya Brooks.

Demographics

Indigenous peoples

At the time of European contact, the dominant ethnic groups in the Caribbean included the Taíno of the Greater Antilles and northern Lesser Antilles, the Island Caribs of the southern Lesser Antilles, and smaller distinct groups such as the Guanahatabey of western Cuba and the Ciguayo and Macorix of eastern Hispaniola. The population of the Caribbean is estimated to have been around 750,000 immediately before European contact, although lower and higher figures are given.[11] After contact, social disruption and epidemic diseases such as smallpox and measles (to which they had no natural immunity)[73] led to a decline in the Amerindian population.[74]

From 1500 to 1800 the population rose as slaves arrived from West Africa[75] such as the Kongo, Igbo, Akan, Fon and Yoruba as well as military prisoners from Ireland, who were deported during the Cromwellian reign in England. Immigrants from Great Britain, Italy, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal and Denmark also arrived, although the mortality rate was high for both groups.[76]

The population is estimated to have reached 2.2 million by 1800.[77] Immigrants from India, China, Indonesia, and other countries arrived in the mid-19th century as indentured servants.[78] After the ending of the Atlantic slave trade, the population increased naturally.[79] The total regional population was estimated at 37.5 million by 2000.[80]

In Haiti and most of the French, Anglophone and Dutch Caribbean, the population is predominantly of African origin; on many islands there are also significant populations of mixed racial origin (including Mulatto-Creole, Dougla, Mestizo, Quadroon, Cholo, Castizo, Criollo, Zambo, Pardo, Asian Latin Americans, Chindian, Cocoa panyols, and Eurasian), as well as populations of European ancestry: Dutch, English, French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish ancestry. Asians, especially those of Chinese, Indian descent, and Javanese Indonesians, form a significant minority in parts of the region. Indians form a plurality of the population in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Suriname. Most of their ancestors arrived in the 19th century as indentured laborers.

The Spanish-speaking Caribbean populations are primarily of European, African, or racially mixed origins. Puerto Rico has a European-identified majority with a tri-racial (mixture of European-African-Native American) population, as well as a large mulatto (European-West African) and West African minority. Cuba has a mixed-race majority, along with a high European minority, and a significant population of African ancestry. The Dominican Republic has the largest mixed-race population, primarily descended from Europeans, West Africans, and Amerindians.

Jamaica has a large African majority, in addition to a significant population of mixed racial background, and has minorities of Chinese, Europeans, Indians, Latinos, Jews, and Arabs. This is a result of years of importation of slaves and indentured laborers, and migration. Most multi-racial Jamaicans refer to themselves as either mixed race or brown. Similar populations can be found in the Caricom states of Belize, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad and Tobago has a multi-racial cosmopolitan society due to the arrivals of Africans, Indians, Chinese, Arabs, Jews, Latinos, and Europeans along with the native indigenous Amerindians population. This multi-racial mix of the Caribbean has created sub-ethnicities that often straddle the boundaries of major ethnicities and include Mulatto-Creole, Mestizo, Pardo, Zambo, Dougla, Chindian, Afro-Asians, Eurasian, Cocoa panyols, and Asian Latinos.

Language

Spanish (64%), French (25%), English (14%), Dutch, Haitian Creole, and Papiamento are the predominant official languages of various countries in the region, although a handful of unique creole languages or dialects can also be found in virtually every Caribbean country. Other languages such as Caribbean Hindustani, Chinese, Javanese, Arabic, Hmong, Amerindian languages, other African languages, other European languages, and other Indian languages can also be found.

Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion in the Caribbean (84.7%).[81] Other religions in the region are Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Rastafari, Buddhism, Chinese folk religion (incl. Taoism and Confucianism), Baháʼí, Jainism, Sikhism, Kebatinan, Traditional African religions, Yoruba (incl. Trinidad Orisha), Afro-American religions, (incl. Santería, Palo, Umbanda, Brujería, Hoodoo, Candomblé, Quimbanda, Orisha, Xangô de Recife, Xangô do Nordeste, Comfa, Espiritismo, Santo Daime, Obeah, Candomblé, Abakuá, Kumina, Winti, Sanse, Cuban Vodú, Dominican Vudú, Louisiana Voodoo, Haitian Vodou, and Vodun).

Politics

Regionalism

Caribbean societies are very different from other Western societies in terms of size, culture, and degree of mobility of their citizens.[82] The current economic and political problems the states face individually are common to all Caribbean states. Regional development has contributed to attempts to subdue current problems and avoid projected problems. From a political and economic perspective, regionalism serves to make Caribbean states active participants in current international affairs through collective coalitions. In 1973, the first political regionalism in the Caribbean Basin was created by advances of the English-speaking Caribbean nations through the institution known as the Caribbean Common Market and Community (CARICOM)[83] which is located in Guyana.

Certain scholars have argued both for and against generalizing the political structures of the Caribbean. On the one hand, the Caribbean states are politically diverse, ranging from communist systems such as Cuba toward more capitalist Westminster-style parliamentary systems as in the Commonwealth Caribbean. Other scholars argue that these differences are superficial and that they tend to undermine commonalities in the various Caribbean states. Contemporary Caribbean systems seem to reflect a "blending of traditional and modern patterns, yielding hybrid systems that exhibit significant structural variations and divergent constitutional traditions yet ultimately appear to function in similar ways."[84] The political systems of the Caribbean states share similar practices.

The influence of regionalism in the Caribbean is often marginalized. Some scholars believe that regionalism cannot exist in the Caribbean because each small state is unique. On the other hand, scholars also suggest that there are commonalities amongst the Caribbean nations that suggest regionalism exists. "Proximity as well as historical ties among the Caribbean nations has led to cooperation as well as a desire for collective action."[85] These attempts at regionalization reflect the nations' desires to compete in the international economic system.[85]

Furthermore, a lack of interest from other major states promoted regionalism in the region. In recent years the Caribbean has suffered from a lack of U.S. interest. "With the end of the Cold War, U.S. security and economic interests have been focused on other areas. As a result, there has been a significant reduction in U.S. aid and investment to the Caribbean."[86] The lack of international support for these small, relatively poor states, helped regionalism prosper.

Another issue of due to the cold war in the Caribbean has been the reduced economic growth of some Caribbean States due to the United States and European Union's allegations of special treatment toward the region by each other.

In counteraction, the European Union claimed that the U.S. in the midst of the cold war, and seeking to promote capitalist economic growth in the region through offshoring of business development and later on offshore financial sector characterized this segment of regional government activity in the Caribbean as an unfair/ Harmful low-tax competition which undercuts the higher taxation rates found in Europe. Much of the U.S. tax code which benefited the Caribbean US eases stance on 'tax havens', was to cull socialist movements in the region, limit Russian financial influence in the area, and firmly integrate the Caribbean into the United States financial system much to the insistence by the E.U. that the low tax rates of the Caribbean for global companies needed to be banned.U.S.-Caribbean Relations

United States-EU trade dispute

The United States President Bill Clinton, backed by American owned banana producers in Central America launched a challenge in the World Trade Organization against the EU over Europe's preferential program, known as the Lomé Convention, which allowed banana exports from the former colonies of the Group of African, Caribbean and Pacific states (ACP) to enter Europe cheaply.[87] The World Trade Organization sided in the United States' favour and the beneficial elements of the convention to African, Caribbean and Pacific states has been partially dismantled and replaced by the Cotonou Agreement.[88]

During the US/EU dispute, the United States imposed large tariffs on European Union goods (up to 100%) to pressure Europe to change the agreement with the Caribbean nations in favour of the Cotonou Agreement.[89]

Farmers in the Caribbean have complained of falling profits and rising costs as the Lomé Convention weakens. Some farmers have faced increased pressure to turn towards the cultivation of marijuana, which has a higher profit margin and fills the sizable demand for these narcotics in North America and Europe.[90][91][92]

Caribbean Financial Action Task Force and Association of Caribbean States

Caribbean nations have also started to more closely cooperate in the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force and other instruments to add oversight of the offshore industry. One of the most important associations that deal with regionalism amongst the nations of the Caribbean Basin has been the Association of Caribbean States (ACS). Proposed by CARICOM in 1992, the ACS soon won the support of the other countries of the region. It was founded in July 1994. The ACS maintains regionalism within the Caribbean on issues unique to the Caribbean Basin. Through coalition building, like the ACS and CARICOM, regionalism has become an undeniable part of the politics and economics of the Caribbean. The successes of region-building initiatives are still debated by scholars, yet regionalism remains prevalent throughout the Caribbean.

Chinese relations

In recent history increasing numbers of countries in the regions have signed on to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative in order to take advantage of the advancing Chinese market and access development loans at rates lower than traditional global institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or World Bank.

Nations in the region which have joined China's global trading network are: Antigua & Barbuda, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad & Tobago.[93] In addition the nations of France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom all of which have a considerable amount of territory in the region are also Belt & Road Initiative area members.

Bolivarian Alliance

The President of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez launched an economic group called the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), which several eastern Caribbean islands joined. In 2012, the nation of Haiti, with 9 million people, became the largest CARICOM nation that sought to join the union.[94]

Regional institutions

Here are some of the bodies that several islands share in collaboration:

- African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States

- Association of Caribbean States (ACS), Trinidad and Tobago

- Caribbean Association of Industry and Commerce (CAIC), Trinidad and Tobago

- Caribbean Association of National Telecommunication Organizations (CANTO), Trinidad and Tobago[95]

- Caribbean Community (CARICOM), Guyana

- Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), Barbados

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDERA), Barbados

- Caribbean Educators Network[96]

- Caribbean Electric Utility Services Corporation (CARILEC), Saint Lucia[97]

- Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC), Barbados and Jamaica

- Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF), Trinidad and Tobago

- Caribbean Food Crops Society, Puerto Rico

- Caribbean Football Union (CFU), Jamaica

- Caribbean Hotel & Tourism Association (CHTA), Florida and Puerto Rico[98]

- Caribbean Initiative (Initiative of the IUCN)

- Caribbean Media Corporation (CMC), Barbados

- Caribbean Programme for Economic Competitiveness (CPEC), Saint Lucia

- Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), Trinidad and Tobago

- Caribbean Regional Environmental Programme (CREP), Barbados[99]

- Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (CRFM), Belize[100]

- Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery (CRNM), Barbados and Dominican Republic[101]

- Caribbean Telecommunications Union (CTU), Trinidad and Tobago

- Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO), Barbados

- Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC)

- Eastern Caribbean Civil Aviation Authority (ECCAA), Antigua and Barbuda

- Eastern Caribbean Telecommunications Authority (ECTEL), Saint Lucia

- Foundation for the Development of Caribbean Children, Barbados

- Group of 77

- Latin America and Caribbean Network Information Centre (LACNIC), Brazil and Uruguay

- Latin American and the Caribbean Economic System, Venezuela

- Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), Saint Lucia

- Small Island Developing States (SIDS),

- United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Chile and Trinidad and Tobago

- University of the West Indies, Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago.[102] In addition, the fourth campus, the Open Campus was formed in June 2008 as a result of an amalgamation of the Board for Non-Campus Countries and Distance Education, Schools of Continuing Studies, the UWI Distance Education Centres and Tertiary Level Units. The Open Campus has 42 physical sites in 16 Anglophone caribbean countries.

- West Indies Cricket Board, Antigua and Barbuda[103]

Cuisine

Favourite or national dishes

- Anguilla – rice, peas and fish

- Antigua and Barbuda – fungee and pepperpot

- Bahamas – Guava duff, Conch Salad, Peas n' Rice, and Conch Fritters

- Barbados – cou-cou and flying fish

- Belize – rice and beans, stew chicken with potato salad ; white rice, stew beans and fry fish with cole slaw

- British Virgin Islands – fish and fungee

- Cayman Islands – turtle stew, turtle steak, grouper

- Colombian Caribbean – rice with coconut milk, arroz con pollo, sancocho, Arab cuisine (due to the large Arab population)

- Cuba – platillo Moros y Cristianos, ropa vieja, lechon, maduros, ajiaco

- Dominica – mountain chicken, rice and peas, dumplings, saltfish, dashin, bakes (fried dumplings), coconut confiture, curry goat, cassava farine, oxtail

- Dominican Republic – arroz con pollo with stewed red kidney beans, pan fried or braised beef, salad/ ensalada de coditos, pastelitos, mangú, sancocho, locrio

- Grenada – oil down, Roti and rice & chicken

- Guyana – roti and curry, pepperpot, cookup rice, methem, pholourie

- Haiti – griot (fried pork) served with du riz a pois or diri ak pwa (rice and beans)

- Jamaica – ackee and saltfish, callaloo, jerk chicken, curry chicken

- Montserrat – Goat water

- Puerto Rico – yellow rice with green pigeon peas, saltfish stew, roasted pork shoulder, chicken fricassée, mofongo, tripe soup, alcapurria, coconut custard, rice pudding, guava turnovers, Mallorca bread

- Saint Kitts and Nevis – goat water, coconut dumplings, spicy plantain, saltfish, breadfruit

- Saint Lucia – callaloo, dal roti, dried and salted cod, green bananas, rice and beans

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines – roasted breadfruit and fried jackfish

- Suriname – brown beans and rice, roti and curry, peanut soup, battered fried plantain with peanut sauce, nasi goreng, moksie alesi, bara, pom

- Trinidad and Tobago – doubles, curry with roti or dal bhat, aloo pie, phulourie, callaloo, bake and shark, curry crab and dumpling

- United States Virgin Islands – stewed goat, oxtail or beef, seafood, callaloo, fungee

See also

- African diaspora

- Afro-Caribbean people

- Anchor coinage

- British African-Caribbean people

- British Indo-Caribbean people

- CONCACAF

- Cricket West Indies

- Council on Hemispheric Affairs

- Hispanic Caribbean

- Hurricanes: Bahama Archipelago, Barbados, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Jamaica, Virgin Islands

- Indian diaspora

- Indo-Caribbean

- Indo-Caribbean American

- NECOBELAC Project

- Non-resident Indian and person of Indian origin

Geography:

Notes

- The Lucayan Archipelago is sometimes excluded from the definition of the "Caribbean" and instead classified as a part of North Atlantic; this is primarily a geological rather than cultural or political distinction.

- Sometimes included.

References

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- McWhorter, John H. (2005). Defining Creole. Oxford University Press US. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-19-516670-5.

- "Cancun Riviera Maya, Hotels and All Inclusive Resorts, Mexican Caribbean Travel". www.mexicancaribbean.com.

- Allsopp, Richard; Allsopp, Jeannette (2003). Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. University of the West Indies Press. p. 136–. ISBN 978-976-640-145-0.

- Engerman, Stanley L. (2000). "A Population History of the Caribbean". In Haines, Michael R.; Steckel, Richard Hall (eds.). A Population History of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 483–528. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7. OCLC 41118518.

- Hillman, Richard S.; D'Agostino, Thomas J., eds. (2003). Understanding the contemporary Caribbean. London, UK: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 978-1588266637. OCLC 300280211.

- Asann, Ridvan (2007). A Brief History of the Caribbean (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8160-3811-4.

- Higman, B. W. (2011). A ConciseHistory of the Caribbean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0521043489.

- "Latin America and the Caribbean | UNDP Climate Change Adaptation". www.adaptation-undp.org. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Lawler, Andrew (23 December 2020). "Invaders nearly wiped out Caribbean's first people long before Spanish came, DNA reveals". National Geographic.

- Williams, Eric (1944). Capitalism and Slavery (Third ed.). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-6370-8. OCLC 1241662726.

- Brinkley, Alan. The Unfinished Nation: a Concise History of the American People. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008. 596. Print.

- Bailey, Thomas Andrew. "A Latin American Protests (1943)." The American Spirit: Since 1865. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. 199. Print.

- Staff, ed. (2021) [1998]. "Monroe Doctrine". www.britannica.com. Britannica. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

Pres. James Monroe in his annual message to Congress. Declaring that the Old World and New World had different systems and must remain distinct spheres, Monroe made four basic points: (1) the United States would not interfere in the internal affairs of or the wars between European powers; (2) the United States recognized and would not interfere with existing colonies and dependencies in the Western Hemisphere; (3) the Western Hemisphere was closed to future colonization; and (4) any attempt by a European power to oppress or control any nation in the Western Hemisphere would be viewed as a hostile act against the United States

- "North America". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia; "... associated with the continent is Greenland, the largest island in the world, and such offshore groups as the Arctic Archipelago, The Bahamas, the Greater and Lesser Antilles, the Queen Charlotte Islands, and the Aleutian Islands," but also "North America is bounded ... on the south by the Caribbean Sea," and "according to some authorities, North America begins not at the Isthmus of Panama but at the narrows of Tehuantepec."

- The World: Geographic Overview, The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency; "North America is commonly understood to include the island of Greenland, the isles of the Caribbean, and to extend south all the way to the Isthmus of Panama."

- The Netherlands Antilles: The joy of six, The Economist Magazine, 29 April 2010

- "Carib". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

inhabited the Lesser Antilles and parts of the neighbouring South American coast at the time of the Spanish conquest.

- Jelly-Shapiro, Joshua (2016). Island People: The Caribbean and the World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 8. ISBN 9780385349765.

- Elster, Charles Harrington. "Caribbean", from The Big Book of Beastly Mispronunciations. p.78. (2d ed. 2005)

- In the early 20th century, only the pronunciation with the primary stress on the third syllable was considered correct, according to Frank Horace Vizetelly, A Desk-Book of Twenty-five Thousand Words Frequently Mispronounced (Funk and Wagnalls, 1917), p. 233.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Johnson, Keith (2011). A Course in Phonetics. Cengage Learning. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-4282-3126-9.

- "Caribbean: Meaning and Definition of | Infoplease". www.infoplease.com.

- Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: Caribbean". www.ahdictionary.com.

- "Definition of CARIBBEAN". www.merriam-webster.com.

- See, e.g., Elster, supra.

- "Caribbean | Definition of Caribbean by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Caribbean". Lexico Dictionaries | English.

- 27 incredibly common spelling mistakes that make you look less intelligent, Mark Abadi, Business Insider

- Oxford Says These 17 Words Are Spelled Wrong Most Often (Out of More Than 2 Billion), By Peter Economy, Inc Magazine

- "Background of the business forum of the Greater Caribbean of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS)". Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). acs-aec.org - "SPP Background". CommerceConnect.gov. Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- "Ecoregions of North America". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "What's the difference between North, Latin, Central, Middle, South, Spanish and Anglo America?". About.com.

- Unless otherwise noted, land area figures are taken from "Demographic Yearbook—Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density" (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Since the Lucayan Archipelago is located in the Atlantic Ocean rather than Caribbean Sea, the Bahamas are part of the West Indies but are not technically part of the Caribbean, although the United Nations groups them with the Caribbean.

- "CBS Statline". opendata.cbs.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- Because of ongoing activity of the Soufriere Hills volcano beginning in July 1995, much of Plymouth was destroyed and government offices were relocated to Brades. Plymouth remains the de jure capital.

- Since the Lucayan Archipelago is located in the Atlantic Ocean rather than Caribbean Sea, the Turks and Caicos Islands are part of the West Indies but are not technically part of the Caribbean, although the United Nations groups them with the Caribbean.

- Dosal, Paul. "THE CARIBBEAN WAR. The United States in the Caribbean, 1898–1998" (PDF). University of South Florida.

- Seabury, Paul; McDougall, Walter A., eds. (1984). The Grenada Papers. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies. ISBN 0-917616-68-5. OCLC 11233840.

- Parameters: Journal of the US Army War College. U.S. Army War College. 1977. p. 13.

- "Foreign Intervention by Cuba" (PDF).

- Dixon, Jeffrey S.; Sarkees, Meredith Reid (2015). A Guide to Intra-state Wars: An Examination of Civil, Regional, and Intercommunal Wars, 1816–2014. CQ Press. p. 624.

- ten Brink, Uri. "Puerto Rico Trench 2003: Cruise Summary Results". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- Datos climatológicos normales y extremos 71–2000 estaciones Sinópticas – tercer trimestre 2019" (in Spanish). Oficina Nacional de Meteorología. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Summary Climatological Normals 1981–2010" (PDF). Departamento Meteorologico Aruba. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Climate Data Aruba". Departamento Meteorologico Aruba. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Average Weather for Mayaguez, PR – Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- "World Weather Information Service – Havana". Cuban Institute of Meteorology. June 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Casa Blanca, Habana, Cuba: Climate, Global Warming, and Daylight Charts and Data". Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Beckford, Clinton L.; Rhiney, Kevon (2016). "Geographies of Globalization, Climate Change and Food and Agriculture in the Caribbean". In Clinton L. Beckford; Kevon Rhiney (eds.). Globalization, Agriculture and Food in the Caribbean. Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-53837-6. ISBN 978-1-137-53837-6.

- Ramón Bueno; Cornella Herzfeld; Elizabeth A. Stanton; Frank Ackerman (May 2008). The Caribbean and climate change: The costs of inaction (PDF).

- Winston Moore; Wayne Elliot; Troy Lorde (2017-04-01). "Climate change, Atlantic storm activity and the regional socio-economic impacts on the Caribbean". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 19 (2): 707–726. doi:10.1007/s10668-016-9763-1. ISSN 1387-585X. S2CID 156828736.

- Sealey-Huggins, Leon (2017-11-02). "'1.5°C to stay alive': climate change, imperialism and justice for the Caribbean". Third World Quarterly. 38 (11): 2444–2463. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1368013.

- BERARDELLI, JEFF (29 August 2020). "Climate change may make extreme hurricane rainfall five times more likely, study says". CBC News. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Clement Lewsey; Gonzalo Cid; Edward Kruse (2004-09-01). "Assessing climate change impacts on coastal infrastructure in the Eastern Caribbean". Marine Policy. 28 (5): 393–409. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2003.10.016.

- Borja G. Reguero; Iñigo J. Losada; Pedro Díaz-Simal; Fernando J. Méndez; Michael W. Beck (2015). "Effects of Climate Change on Exposure to Coastal Flooding in Latin America and the Caribbean". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0133409. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133409. PMC 4503776. PMID 26177285.

- Mark Spalding; Corinna Ravilious; Edmund Peter Green (10 September 2001). World Atlas of Coral Reefs. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23255-6. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- Littler, D. and Littler, M. (2000) Caribbean Reef Plants. OffShore Graphics, Inc., ISBN 0967890101.

- Minter, D.W., Rodríguez Hernández, M. and Mena Portales, J. (2001) Fungi of the Caribbean. An annotated checklist. PDMS Publishing, ISBN 0-9540169-0-4.

- Kirk, P. M.; Ainsworth, Geoffrey Clough (2008). Ainsworth & Bisby's Dictionary of the Fungi. CABI. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- "Fungi of Cuba – potential endemics". cybertruffle.org.uk. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Fungi of Puerto Rico – potential endemics". cybertruffle.org.uk. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Fungi of the Dominican Republic – potential endemics". cybertruffle.org.uk. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Fungi of Trinidad & Tobago – potential endemics". cybertruffle.org.uk. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "North American Extinctions v. World". Thegreatstory.org. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- "Caribbean Coral Reefs". coral-reef-info.com. 9 November 2020.

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Mumby, P. J.; Hooten, A. J.; Steneck, R. S.; Greenfield, P.; Gomez, E.; Harvell, C. D.; Sale, P. F.; et al. (2007). "Coral Reefs Under Rapid Climate Change and Ocean Acidification". Science. 318 (5857): 1737–42. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1737H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.702.1733. doi:10.1126/science.1152509. PMID 18079392. S2CID 12607336.

- "Caribbean coral reefs may disappear within 20 years: Report". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- Rogoziński, Jan (2000). A Brief History of the Caribbean. Penguin. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-452-28193-6.

- Rogoziński, Jan (2000). A Brief History of the Caribbean. Penguin. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-452-28193-6.

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.

- Engerman, p. 486

- The Sugar Revolutions and Slavery, U.S. Library of Congress

- Engerman, pp. 488–492

- Engerman, Figure 11.1

- Engerman, pp. 501–502

- Engerman, pp. 504, 511

- Table A.2, Database documentation, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) Population Database, version 3, International Center for Tropical Agriculture, 2005. Accessed on line 20 February 2008.

- Christianity in its Global Context Archived 2013-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Gowricharn, Ruben. Caribbean Transnationalism: Migration, Pluralization, and Social Cohesion, Lanham: Lexington Books, 2006. p. 5 ISBN 0-7391-1167-1

- Hillman, p. 150

- Hillman, p. 165

- Serbin, Andres (1994). "Towards an Association of Caribbean States: Raising Some Awkward Questions". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 36 (4): 61–90. doi:10.2307/166319. JSTOR 166319.

- Hillman, p. 123

- "The U.S.-EU Banana Agreement". Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) See also: "Dominica: Poverty and Potential". BBC. 16 May 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2008. - "WTO rules against EU banana import practices". Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). eubusiness.com (29 November 2007) - "No truce in banana war". BBC News. 8 March 1999. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- "World: Americas St Vincent hit by banana war". BBC News. 13 March 1999. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- "Concern for Caribbean farmers". Bbc.co.uk. 7 January 2005. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Barkham, Patrick (5 March 1999). "The banana wars explained". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Staff writer (13 June 2019). "China's Belt & Road – The Caribbean & West Indies". Silk Road Briefing. Dezan Shira & Associates. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Edmonds, Kevin (6 March 2012). "ALBA Expands its Allies in the Caribbean". Venezuela Analysis. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- "CANTO Caribbean portal". Canto.org. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "Caribbean Educators Network". CEN. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "Carilec". Carilec.com. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "About Us". Caribbean Hotel & Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- "Caribbean Regional Environmental Programme". Crepnet.net. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism". Caricom-fisheries.com. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "Official website of the RNM". Crnm.org. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "University of the West Indies". Uwi.edu. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "West Indies Cricket Board WICB Official Website". Windiescricket.com. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

Bibliography

- Engerman, Stanley L. "A Population History of the Caribbean", pp. 483–528 in A Population History of North America Michael R. Haines and Richard Hall Steckel (Eds.), Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-49666-7.

- Hillman, Richard S., and Thomas J. D'agostino, eds. Understanding the Contemporary Caribbean, London: Lynne Rienner, 2003 ISBN 1-58826-663-X.

Further reading

- Develtere, Patrick R. 1994. "Co-operation and development: With special reference to the experience of the Commonwealth Caribbean" ACCO, ISBN 90-334-3181-5

- Gowricharn, Ruben. Caribbean Transnationalism: Migration, Pluralization, and Social Cohesion. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2006.

- Henke, Holger, and Fred Reno, eds. Modern Political Culture in the Caribbean. Kingston: University of West Indies Press, 2003.

- Heuman, Gad. The Caribbean: Brief Histories. London: A Hodder Arnold Publication, 2006.

- de Kadt, Emanuel, (editor). Patterns of foreign influence in the Caribbean, Oxford University Press, 1972.

- Knight, Franklin W. The Modern Caribbean (University of North Carolina Press, 1989).

- Kurlansky, Mark. 1992. A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny. Addison-Wesley Publishing. ISBN 0-201-52396-5

- Langley, Lester D. The United States and the Caribbean in the Twentieth Century. London: University of Georgia Press, 1989.

- Maingot, Anthony P. The United States and the Caribbean: Challenges of an Asymmetrical Relationship. Westview Press, 1994.

- Palmie, Stephan, and Francisco A. Scarano, eds. The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its Peoples (University of Chicago Press; 2011); 660 pp.; writings on the region since the pre-Columbia era.

- Ramnarine, Tina K. Beautiful Cosmos: Performance and Belonging in the Caribbean Diaspora. London, Pluto Press, 2007.

- Rowntree, Lester/Martin Lewis/Marie Price/William Wyckoff. Diversity Amid Globalization: World Regions, Environment, Development, 4th edition, 2008.

.jpg.webp)